What you say matters: verbal and visual codes in memory

Working memory is defined as the cognitive processes engaged in the storage of a limited amount of information while we are processing new information simultaneously. It is equivalent to the term short-term memory although it emphasizes the processing and updating of information and not only its storage.

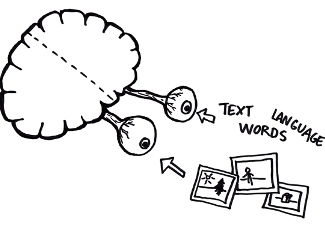

The most widely accepted theoretical model is the one formulated by Baddeley and Hitch in 1974, which has become a framework for understanding the role of short-term memory in a large number of complex cognitive tasks such as reading or learning new vocabulary. These authors define this kind of memory as a limited capacity system that consists of three components, an attentional controller and two subsystems, one that stores and processes verbal information, and another for the visual and spatial material (features of objects such as colour, shape or location).

Despite being differentiated components the question that arises is how they interact, and this is the aim of our research, that is, to what extent are verbal codes involved in the retention of visual stimuli such as coloured triangles or circles? Do we retain a triangle only visually, or do we retain the word “triangle” instead?

In order to minimize verbal coding of visual objects, we manipulated the verbal component by repeating words out loud so that the verbal coding of visual stimuli is prevented. For example, if one articulates the words “one, two, three” repeatedly while trying to memorize a red triangle, it is assumed that retaining the words “red triangle” will be more difficult than retaining the visual image evoked by the stimulus.

But what will happen if we repeat the name of a coloured shape (that is not part of the to-be-remembered set) instead of an irrelevant word (Condition 1, e.g “brown hexagon”) while at the same time we must retain 4 different coloured shapes for further recall? And, will a pair of concrete, highly imageable words (Condition 2, e.g “big table”) cause more interference than repeating a pair of abstract words (Condition 3, e.g. “critical event”)? In sum, the aim of the experiment was to assess whether the content of what we say out loud has differential effects on the recall of visual stimuli, which is a novel approach compared to previous studies that have focused on the interference of verbal material but not on its meaning.

Results showed that articulating words has negative effects on the recall of coloured shapes, which suggests that visual working memory is partly supported by verbal codes. However, interference is not only verbal because if this was the case, any experimental condition would have affected visual recall in the same extent. Results indicated that there were differences between conditions 1 and 2, and condition 3.

How do these conditions differ? Conditions 1 and 2 (that were more interfering) imply the repetition of words that have a visual representation in long term memory: A brown hexagon, a big table etc. are concrete concepts that can be readily imagined. However, condition 3, consists of repeating abstract words that do not have any clear visual correspondence (i.e a “critical event” does not easily evoke a mental image).

Therefore, repeating imageable words causes a greater interference on the recall of visual stimuli compared to words that cannot be easily visualized. This finding indicates that the articulation of concepts somehow activates a visual representation that is already stored in long term memory, and this visual concept “competes” with the to-be-remembered coloured shapes (probably due to the capacity limitations of visual working memory). However, articulating a name of a colour and a shape does not affect recall in a higher extent than repeating concrete words, so it seems that the fact that the words are semantically related to the visual stimuli does not impair recall specifically.

The main conclusion is that when we articulate words, the probability of encode visual objects verbally is reduced, but what really causes an interference is the competition between visual representations generated by repetition and the ones that arise from the to-be-remembered items, as they both rely in a visual code. The research paper emphasizes the importance of the content of the words used to occupy the verbal component, the interaction between visual and verbal codes in working memory and the role of long term memory.

References

Judit Mate; Richard J. Allen; Josep Baqués

What you say matters: Exploring visual–verbal interactions in visual working memory

The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. Volume 65, Issue 3, pages 395-400, 2012.